Terms of Endearment (1983)

Directed and co-written by James L. Brooks

Based on the novel by, and co-written by, Larry McMurtry

Larry McMurtry was a prolific writer, author of something like 20 novels, many of which were set in either the Old West of cowboy times, or in modern Texas. Of the latter, three novels published early in his career as a writer stand out: known as the Houston series, they are Moving On (1970), All My Friends are Going to Be Strangers (1972), and Terms of Endearment (1975).1 The first two — one 800-page doorstop and one 250-page tidy spinoff — are about Rice University grad students Danny and Flap, their wives Patsy and Emma, and a cast of characters they run into in Texas — a rodeo star, a rodeo clown, a screenwriter taking notes for a movie about the broncbuster, and for laughs, an effete professor type who might be played by Terry-Thomas if a movie had ever been made of the first two books. But they were rather niche in their concerns, and not many people can say they made it through Moving On all the way, much less its follow-up.

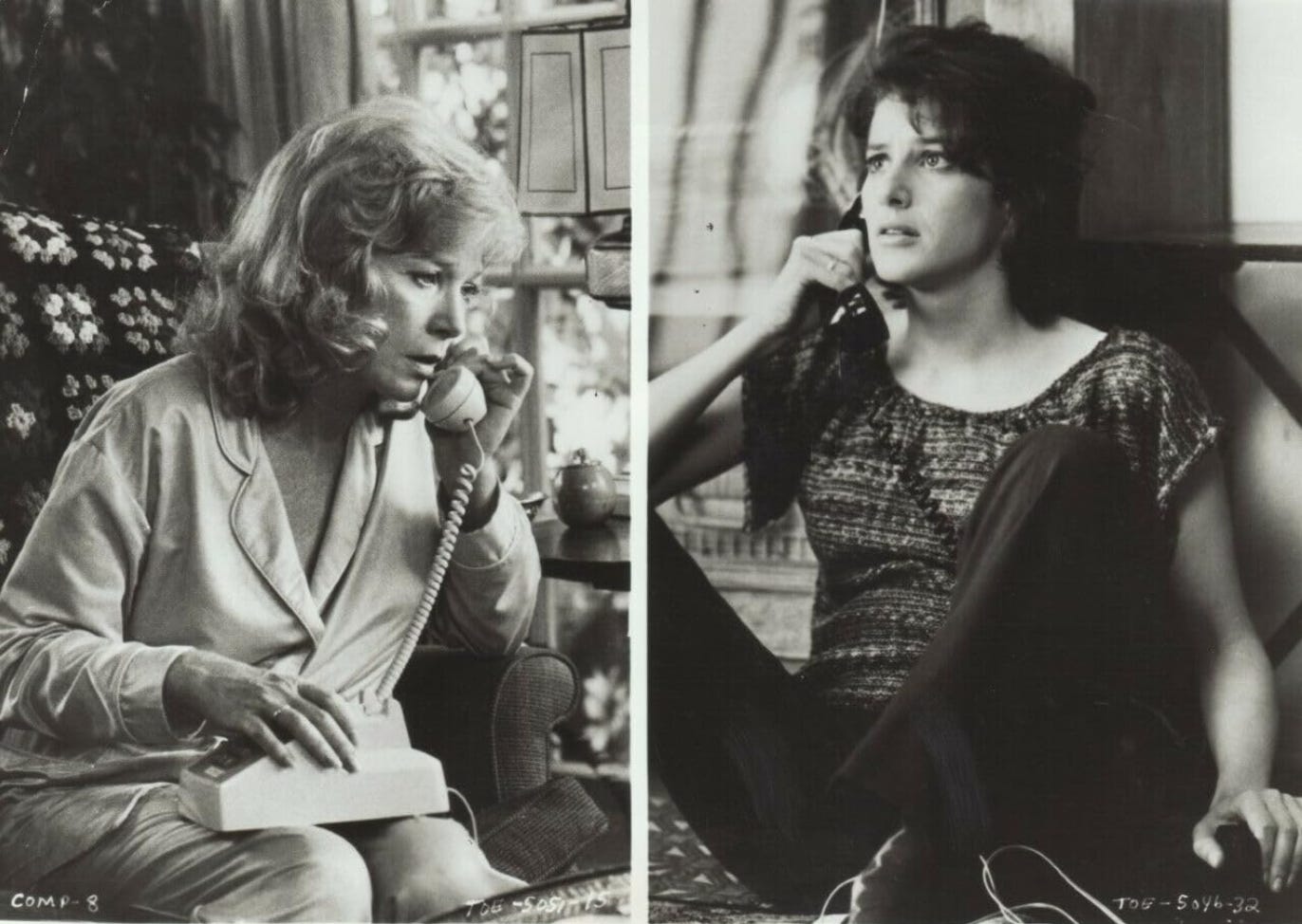

The third, though, Terms of Endearment, was a best-seller and was promptly made into a dramedy starring Shirley MacLaine, Debra Winger, Jeff Daniels and Jack Nicholson. A lot of people saw the film version, which was nominated for 11 Oscars and won 5, including Best Picture, Actress (MacLaine) and actor (Nicholson).

As I wrote in my essay about Texas and “The Sugarland Express,” I spent my teenage years in a Houston suburb adjacent to the NASA headquarters, so I know a little bit about Houston and astronauts, much less about grad students (I didn’t understand such creatures existed before reading McMurtry at age 16 or so) and even less about being the parent of small children, and that last bit is an important element of the three books. What was striking, to me as a reader, and what comes through in this 1983 film — and probably the element his fiction is best known for — is McMurtry’s sympathy toward, and understanding of, women’s lives.

Yes, the weepy part in act IV is what people remember most about the film. But one thing that McMurtry and director and co-writer James L. Brooks understood was that female characters can and should be complex, and be able to juggle several subplots at once. Brooks, a popular and successful producer-screenwriter who’s still working today, only directed seven feature films (among Best Director Oscar winners, he may be the director who helmed the fewest), but among them are “Terms of Endearment” and “Broadcast News.” Add to that the women-centered TV series he created: “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” and two spinoffs, “Rhoda” and “Lou Grant,” as well as “The Tracy Ullman Show.” (Not to mention “The Simpsons.”)

So what we see here is not just Debra Winger's character Emma achieving a degree of independence boffing John Lithgow2 and then dying of metastatic cancer. It’s Emma as an assertive straight woman in the 1970s during the blooming of second-wave feminism. It’s Shirley MacLaine's character, her mother, River Oaks widow Aurora Greenway — just one of McMurtry’s absolutely perfect character names3 -- having the self-respect and independence necessary to politely host a trio of suitors as party guests without giving encouragement to any of them. It’s Aurora then being complex enough to have her third act be with none of the suitors but with her next door retired astronaut neighbor Garrett (Jack Nicholson), who is the opposite of them — and insisting that his character grow and change to adapt to her, as much as she adapts to him.

It’s observing motherhood, and young children, closely and seriously enough to understand how they interact in a wide spectrum of parenting moments. McMurtry wasn’t really feminist in the contemporary sense; he seemed to like his women characters best if they had a child on their hip. But he regards them highly enough to make them rounded characters. He even gives Emma and Flap’s oldest child Tommy — who starts as a sweet toddler and grows into a resentful 11-year-old — a character arc.

These are the ingredients of a script capable of not only showing women’s lives, but valorizing them, and not sentimentally. (Yes, the sentimentality does come at the end, and arguments have been made that a film that purports to celebrate the independence of women humbles them and kills the most independent one. I would argue that the fact their independence is displayed at all, and in a multitude of ways, outweighs the weaknesses.) Parenting is work, McMurtry reports, and we should take the work seriously.

Add to that the fact — actually I don’t know that this is a fact but I feel it is — that this was one of the first Hollywood movies to not only say the word “cancer” out loud, but have a character who insists on saying it out loud, to cast light on it. She won't be just shoved into a sick bed for her last days, but lives as normal a life as she can, openly, as a woman with cancer. (Ironically, everyone in her circle gets the memo, such that a total stranger comes up to her at a party and brightly says, by way of a conversational opener: “Patsy tells us you have cancer!”)

To Brooks’ credit, the ending, despite its four-hankie rating from the New York Times reviewer Janet Maslin4, is understated. It shortens the part of McMurtry’s book devoted to Emma’s illness, which is also understated, in its own way. After many grueling pages describing Emma’s physical and spiritual pain, and her mother finally arriving at a place of compassion, McMurtry ends the sequence with a single, earthshaking, one-sentence paragraph: “Several weeks later she died in bed.”

So, all the pain and sorrow contained in the previous thirty or so pages, times “several weeks.” It was the first time I, as a teenage reader, understood the principles of both understatement and compression.

But I think the reason “Terms of Endearment” won several major awards including Best Picture (defeating the equally epic Philip Kaufman’s “The Right Stuff,” which was also about astronauts) — the reason it escaped being characterized as merely a women’s picture — is Jack Nicholson. He is a scoundrel, a cur, a ridiculous figure, and a sex symbol all at the same time. Every moment he’s onscreen, viewers ready themselves for some kind of jolt, because you never know what he’s going to do. He smirks and pranks his way through a good 45 minutes of screen time, trying to get the straitlaced Aurora to loosen up:

Garrett: I think we're going to have to get drunk.

Aurora: I don't get drunk, and I don't care for escorts who do.

Garrett: You got me into this. You're just gonna have to trust me about this one thing... (She shoots him a deadpan look.) (Sighing:) You'll need a lot of drinks.

Aurora: To break the ice?

Garrett: To kill the BUG that you have up your ASS!

He is outrageous in the best way possible to be (for a character in a movie): he threatens every second to disrupt the equilibrium of polite society. Think of Tom Hulce in “Amadeus” or Judy Holliday in “Born Yesterday” or James Cagney in “White Heat.” (Cagney: “Top of the world, Ma!!” Nicholson: “Wind in the hair! Lead in the pencil! Feet controlling the universe!”)

But Aurora is his equal, and she has one thing that Garrett, with his sports car and his women (a date is usually two or three of them to one of him) will never have: a family. He bows out, saying he will never be right for her. But in the end, when she needs support, he shows up.

As a work about Texas, "Terms of Endearment,” novel and film, have the disadvantage of being partly set in Des Moines and in Kearney, Neb., two minor academic outposts where Emma’s mediocre professor husband Flap (Jeff Daniels) finds work. And the film never properly instructs us in the Montrose district5 where Flap and Emma start out in what is practically a shack, or in the old-money River Oaks neighborhood where Aurora lives in a mansion, though any Houstonian of the day knew them well. As someone who lived for four years in Houston’s suburbs and then matriculated at the U of Texas in Austin, I instantly recognized the shack; I rented places like it in Austin. As for the retired astronaut setting up shop in River Oaks, readers and viewers allow it, but also know that no astronaut still working at NASA would live so far from its campus. Even then it would have been a commute of at least 45 minutes. No, the astronauts and their families lived (and still do) in anodyne suburban developments with names like El Lago and Clear Lake Forest. I went to high school with their kids, about whom was nothing special, though they were granted a little extra space.

Also to read: New York Times, Sep. 14, 2017 “After the Hurricane [Harvey] Winds Die Down, Larry McMurtry’s Houston Trilogy Lives On”

Three additional novels, published in later years, visit some of the characters decades after the events in the first three.

Lithgow’s small town loan officer — part sad puppy dog, part exhausted but philandering husband — made me realize that it was he who should have played the Professor of Hitler Studies in “White Noise” (if that film had been made in 1983).

Garrett Breedlove the astronaut; Flap Horton the mediocre English PhD; Vernon Dahlart the hapless suitor of Aurora

The Montrose is Houston’s bohemian neighborhood, home to a succession of artists, writers, hippies, and queers; no article captures it better than this 1973 piece by Al Reinert in the just-born Texas Monthly magazine, written as McMurtry was working on Terms of Endearment.