Welcome back, readers. This is the first review posted since the election.

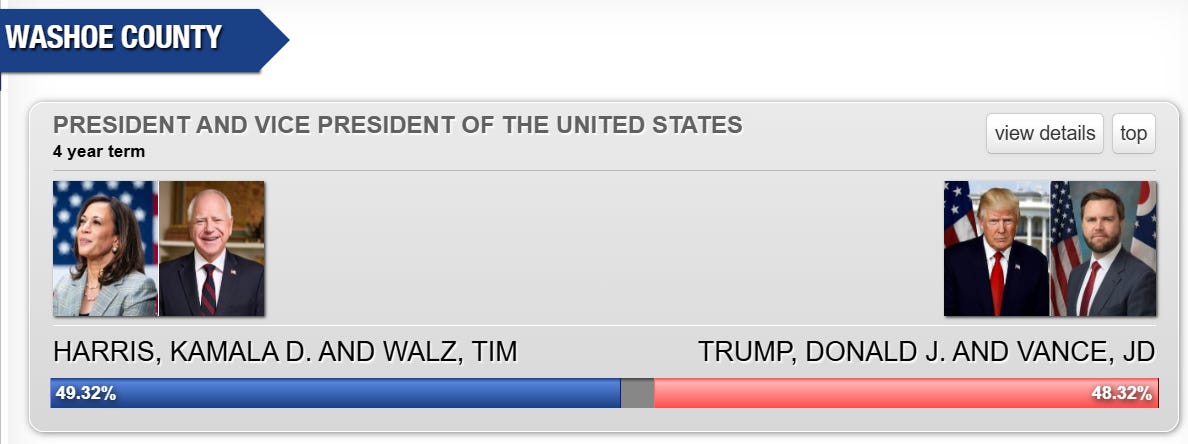

I paused writing about movies to work as a Harris campaign volunteer over the last three months. I worked hard every day and I’m proud of what our Northern Nevada team was able to do: we managed to re-elect our Democratic senator, Jacky Rosen, and several Dems in the statehouse. And at the last minute, Washoe Co., home to Reno, turned blue, as it was in 2016 and 2020.

Now, post-election, I’m looking for new ways to activist. I’m also going back to writing about movies. It’s good for my writing, good for my psyche to have something to focus on besides politics and the coming disasters. (I now understand why Depression-era moviegoers loved escapist fare.)

Strangely, during the campaign, I got several new subscribers (welcome and thank you!) even though I wasn’t publishing consistently. I don’t know how that happened, but I hope you all enjoy these reviews.

Anora (2024)

Written and directed by Sean Baker

Billionaires shouldn’t exist. I take that as an article of belief. And I expect that keeping that dictum in mind is going to be helpful in the next few years, as the U.S. is ruled by one and controlled in various ways by many others.

When I was working on the Harris campaign, one of my pitches was to contrast Kamala Harris’s middle-class, raised-by-a-single-mom background with Trump’s. “He has never worried about putting food on the table, or how to pay for health insurance, or had to choose between buying medicine and buying gas to go to work. He doesn’t understand the lives of normal people. Wouldn’t you rather have a president who does?”

I convinced myself. Who knows if I convinced anyone else; in any case, the overall results are clear. Americans chose the billionaire.

And the American fascination with billionaires has become cult-like. Trump aside, take a look at the cult of personality around Elon Musk. A million men practically worship him and everything he says and does, and seek to emulate him, each in his paltry and pathetic way.

This fascination finds its way into movies, where “billionaire” is shorthand for introducing a plot element for which it’s important that money is no object. Take, for example, the film “Contact,” in which a Japanese billionaire defense contractor builds not one (paid for by the U.S. government, presumably) but two massive devices capable of penetrating — as Kurt Vonnegut dubbed it — the chrono-synclastic infundibulum and projecting Jody Foster’s astronaut into another realm. Without the billionaire, the film lacks a third act.

But even billionaires have to fuck.

You could analyze sex work in a lot of ways. Depending on whether you’re an economist, a public health expert, a cop, a feminist, there’s something there to dig into. Take, for example, the ways that sex workers — or their pimps and other exploitative go-betweens — set and negotiate prices. Belying the stereotype that they are stupid or lack agency, sex workers perform a range of calculations on the fly, pricing in dynamic factors such as supply and demand, the location of the work, how comfortable or safe the venue is, which sexual acts are to be performed, and many other factors. It’s an admirable skill, and much in demand in many areas of the workforce, such as sales.

Hidden in the eventual price is other work just as vital to the job, namely the emotional labor performed by the worker, who typically must flatter the customer and pretend to be aroused. This work is familiar to women in much of their work no matter what it is. When I was getting PT for a shoulder injury, I noticed that my young, female therapist put at least as much effort into encouraging me while I did exercises as she did evaluating me, teaching the exercises, or manipulating my limbs.

Finally I said “Wow, you really have to do a lot of emotional labor in this job.”

She sighed. “Sometimes I come home from a shift and I can’t even talk to my roommates. I’m just worn out by it.”

You know who isn’t worn out by their jobs? The rich. If they have a job at all. What, for example, would you say is the job of Jeff Bezos, for example — or any member of the Walton family that owns Walmart? Who knows, right? But you can be sure of one thing: they are not tired at the end of the day.

“Anora” is about a stripper who meets not a billionaire, but — what’s even better — the billionaire’s wastrel son. To clearly illustrate the encounter and what’s at stake, the first part of the film delves deeply into what sex work is like.

Sex work is a thing that generations of male filmmakers have been fascinated with. Fellini (“Nights of Cabiria”), Godard (“Vivre sa Vie”), Buñuel (“Belle de Jour”), Scorsese (“Taxi Driver”), Wim Wenders (“Paris, Texas”), Paul Shrader (“Hardcore” and “American Gigolo”) and Pedro Almodóvar (“All About My Mother“) are some of the great directors who made films in which sex work was central for a character or the plot (many more have been made by hacks — see Paul Verhoven, “Showgirls”).

But whether or not a movie is made by a great director, the vision of sex work is usually the same. The film tries to demystify the workings of the life of a stripper or hooker enough to show her motivation and degree of success at the job, while simultaneously projecting a tantalizing illusion of sexiness and release.

“Poor Things,” the 2023 hit based on a novel by Alasdair Gray, an elderly Scot, and helmed by horror director Yorgos Lanthimos, typifies the approach. The protagonist, a Pygmalion’s puppet figure, expresses her agency by overly enjoying sex while Victorian; later, she becomes a prostitute in a Parisian brothel for the experience. One can see the movie straining to make her a feminist character; and it succeeds, if one defines feminism as “giving yourself the permission to enjoy sex” and “choosing to be a sex worker less out of basic need than curiosity,” the latter being an unrealistic projection. The sheer danger of a woman having an adventuresome sexual life during a time when tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases were incurable is not mentioned, because the movie is a rapt fantasy and not serious about its points. As Mick LaSalle wrote in the San Francisco Chronicle:

If Bella worked in a Belle Epoque brothel, she’d have been in debt — for her clothes, for her room and board — before she saw her first customer, and she’d never regain her agency. Moreover, she would almost certainly get syphilis and be physically compromised for the rest of her life. The movie’s thesis — that if Bella simply doesn’t mind the things that another woman would mind, she can conquer men and triumph in life — is absolute nonsense for that era.

Like “Poor Things,” “Anora” sets out to treat its protagonist — stage name Ani — with respect. We see, at length, a few evenings at a strip club called Headquarters, where she performs a couple of numbers on stage, then drifts through the crowded club finding men who will pay her for various forms of a lap dance. These can range into the hundreds of dollars, and are cash only; when one customer protests that he has only credit cards, she leads him to the club’s ATM. (I couldn’t help saying out loud “No! Never go to the ATM!”)

This introduction to Anora makes it clear that while she is average-looking, she makes the most of what she has through makeup and costumes; she possesses impressive athletic physical skill and, above all, performs the essential emotional labor to a T. To its credit, the film makes it clear that, for workers, the job is not the salacious experience that the customers are led to see. It’s just work that they need to perform in order to survive. They’re certainly not doing it, like Bella in “Poor Things,” out of curiosity and a thirst for experience.

There she meets Ivan, happy-dumbass son of an extremely wealthy Russian oligarch (drug dealer? arms dealer? it doesn’t matter) named Zakharov. Ivan apparently knows nothing about the family business, but he does know how to be a deep-pocketed strip club customer. After the theater of the lap dance, he brings what was doubtlessly a very expensive evening to a close by asking Anora the crucial question “Do you work outside the club?” — which means, of course, “We observe the rule that there’s no actual sex in the club, so let’s meet in a day or two to have actual sex, for which I will pay you well.” And when that’s done, at a subsequent visit to the forcefully gauche mansion owned by his unseen father, Ivan wants to see her more and more.

The film is more or less silent on Ivan’s motivation, but it’s clear from the script: he is used to having his desires and whims fulfilled, and has the money to pay people to do so. Why else be a billionaire, if not to satisfy one’s desires?

In addition, there’s something about paying for sex that is addictive — it’s a combination of “Oh look, I can get whatever I want, with enough money” and “What more can I get away with? Will enough money tempt the girls to break the rules?”1

Needless to say, the dancers are only too happy to encourage this behavior. So a paid-for hour becomes more and longer dates, and after a blisteringly wild New Year’s Eve party at the house, Ivan asks her if she’d like to “be my girlfriend for a week.” He proposes paying $10,000, and after a pause, she tells him it’ll be $15,000. (He instantly agrees, then adds that he would have agreed to $30,000. This is a telling moment, and perhaps the only one during their whole encounter where Ivan and Anora are operating on the same level2 — a moment familiar to salespeople, where the tension of a negotiation is relieved by agreeing on a price, after which each party drops the mask required for the negotiation and shows a bit of their real selves. The similarity to coitus and its aftermath is obvious.)

I was reminded of Wayne Wang’s “The Center of the World” (2001). In that film, a similarly callow (but much less fun) tech bro (Shane Edelman) offers the same sum to a stripper (Molly Parker) to accompany him for a weekend in Las Vegas. She agrees, but only if the fee does not include sex, which seems fair. Watching “Anora,” I was a little shocked when I heard Ivan offer 10K. The price couldn’t possibly have stayed the same over more than 20 years; more likely, it’s a failure of imagination by the movie’s writer-director Sean Baker.

These sums seem impressive to Anora, who probably brings home $2000 on a really good night. But keep in mind who she’s dealing with here. Ten, or thirty, thousand dollars is pocket change for Ivan, even if he never worked a day in his life for it. (To be clear, neither did his family. You don’t become a billionaire by working, but by cheating and exploiting people; even, like Trump, simply not paying them at all. What are they going to do?)

In any case, Ivan and Anora are off to Las Vegas where, obeying the same just-keep-ordering-more impulse that led to him proposing the trip, Ivan does the thing that apparently occurs to many people when they’re having a great time in Las Vegas: get married.

Anora, who has seemed like she’s having a terrific time so far, now seems genuinely overjoyed by achieving what men imagine to be every sex worker’s dream: marriage to a wealthy man. On their return to New York, she makes a big show of retrieving her stuff from the strip club; one dancer even says that Anora has “won the lottery” that they all aspire to (or at least writer-director Baker imagines that they do).

It’s certainly true that Anora is just doing what ho’s are expected to do: become expert at separating a man from his cash, and if he’s a young guy who can fuck, so much the better. But while their sex is frequent and energetic, zero time is spent on her pleasure; Ivan never goes down on her, in fact there’s no oral sex in the film at all. My friend S. pointed out that they don’t even kiss?

This seems to emphasize the purely transactional nature of their relationship: he pays, she fucks him, and her pleasure doesn’t matter one bit. It doesn’t even matter to her. Their marriage is just an extension of this ethos. End of Act I.

Act II is devoted to a tumultuous intervention by a man named Toros (Karren Karagulian), an employee of Ivan’s father, who has been responsible for keeping Ivan out of trouble since the heir was in single digits. Zharkov Senior, and especially Ivan’s mother (Darya Ekamasova), cannot accept the fact that their son, dissolute though he may be, has married a girl who is, in their eyes, a common prostitute. Dad sends Toros to have the marriage annulled and to get Ivan back on a plane to Russia.

First Toros, comically delayed by a prior commitment in which he is supposed to become an infant’s godfather, dispatches two men to the mansion. We expect them to be real thugs, but both Garnick (Vache Tovmasyan) and Igor (Yura Borisov) are reluctant to get tough. Their attempt to extract the scrawny Ivan with little ado turns, thanks to Anora, into a screaming match. Ivan escapes and Anora more or less kicks both their asses, at least at first, nearly overpowering the men. (After taking a few direct punches from her, Igor rubs his jaw and says, “Hmm, impressive.” Game recognizes game.) This wild scene is one of the funniest extended pieces of slapstick comedy I’ve seen in many years, and the film itself, which has been merely an elaborate post-pandemic romcom up to this point, becomes something more — a work of cinema. Sean Baker really shows how talented a director he is here.

The remainder of Act II is a madcap search for Ivan though Queens and Manhattan. It’s during this part that a subtle ploy begins to emerge: the smaller and seemingly less invested of the heavies, Igor, is shown studying Anora in slack moments. He’s not falling in love with her, he’s just watching her intently. At first this is to prevent her from escaping, but soon the viewer sees that Igor is watching her with a sense of respect and even what I interpreted as compassion. To Toros, she is just a means to the end of locating Ivan; the other thug, Garnick, is still licking his wounds.

Igor (“Hmm, impressive”) sees a fellow street fighter. He remains almost silent, grudgingly going along with it all, but at the same time becoming very subtly … not protective of Anora, really, but very aware of where she’s at emotionally. He has become invested in her getting through this still holding on to a little dignity.

As this part of the movie goes along, he recognizes more and more of himself in her. Both of them are essentially pawns at the beck and call, or abrupt dismissal, of the family Zakharov. Both of them are slated for dismissal, though Anora has a never-give-up streak that motivates her through the night of the search. Though she’s cooperating now, she thinks this is temporary. She doesn’t realize how little power or agency she still has, in the larger scheme of things which is ruled by the Zakharovs. The billionaires.

Spoilers follow!

In Act III, the search has finally been successful. They’ve found Ivan. His parents shortly arrive on scene in a private jet.

Let’s cut to the last scene. The parents — the real billionaires — have won, they’re on their jet back to Russia with Ivan. Tores assigns Igor to take Anora to a bank to pay her an agreed-upon fee (again, $10,000) for cooperating with the family in the end, and then to take her home to Queens.

At the last moment, before she can leave the car, he opens his hand: it’s the wedding ring that Ivan had purchased for her and which Toros stripped off her finger and handed to Igor for safekeeping.

In the passenger seat, Anora sits brooding for a moment. Then she wordlessly climbs onto Igor’s lap and fucks him. The scene lasts just long enough for the viewer to understand why she has done this: she’s still transactional. After she received the 10K, they were square. The ring upsets the balance; she has to do something in payment.3

It’s a brutal moment. I saw her need to assert control as one of the psychic costs of sex work, but it strikes the viewer as a true one. You keep the customers in bounds. In this sense, Anora’s stripper credo triumphs even over that of the billionaires; there’s nothing stopping her from going right back to sex work, and she’s $25,000 ahead. And the Zharkovs have to go live in fucking Russia.

I also reviewed “Compartment No. 6,” a Finnish film in which Borisov is also a standout.

Because despite the bacchanalian atmosphere, there are rules galore. A customer may do only what the dancer explicitly permits. You want to touch any part of them, even a knee? You better ask first, lest you be told, as depicted in one moment, to literally sit on your hands. The bacchanal, the lap dance itself, the dancer’s seeming enjoyment, it’s all theater.

I’m grateful to my friend S., an insightful filmgoer, for this insight and others in this review.

S. said she saw this action not as transactional but as Anora “taking the upper hand. in the situation, and that the key moment was the kiss that Igor attempts after he comes.

S. added that she highly recommends “Red Rocket” (2021) by the same filmmaker.

Loved this piece, Mark. So true that billionaires have never had to endure what it's like to live paycheck to paycheck, praying that your kid doesn't get sick, or your washing machine goes out, or your car needs a new engine. It reminded me of something Kara Swisher said in a recent podcast when talking to Ta-Nehisi Coates about why tech bros are so in favor of zero moderation on their platforms. She said, "Because the people who design the systems never felt unsafe a day in their lives." As a woman, she said, when she walks down a street at night, she always checks her surroundings. Ask any woman, they will tell you the same. So true. Billionaires and White men in general, don't know what it's like to fear for one's life on the daily. Women are often afraid--of men.